Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM)

What Doug Trumbull taught me about End Titles

Star fields and end titles have something in common: tiny points of light moving at 24p through a sea of black.

I was lucky enough to catch film legend Doug Trumbull speak at Abel Cine in New York several years ago. Naturally our conversation afterwards turned to end titles. Well, not exactly. Mr. Trumbull had been discussing the star fields in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, but we were building Endcrawl at the time, and Mr. Trumbull did provide a minor epiphany.

While he was working on the visual effects for 2001, Trumbull noticed that panning the camera too quickly across his star fields—small points of white on a black sky—caused the eye to see each star double, triple, quadruple. This was a product of a perfectly high-contrast image combined with 24 fps capture and projection.

The minor epiphany: end titles are essentially the same thing, just small white symbols moving through an ocean of black. They move with geometrically perfect motion, and whether on 35mm film or DCP, they’re still doing it at 24 frames per second.

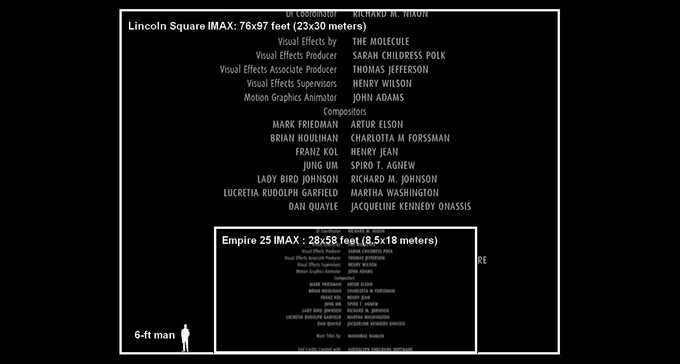

These factors all conspire to leave an after-image on the human retina, so that even when the source material is perfectly smooth, our eyes perceive a stutter. In fact, the larger the screen, the worse the effect. In your 1985 living room, you probably never noticed it, but at the Lincoln Square IMAX theater on 68th Street in Manhattan, those letters are jumping between 3 and 5 inches every frame—6 to 10 feet per second. That gets pretty choppy.

So how can we make the last five minutes of your film look good?

Some designers try adding motion blur. This makes some kind of mad sense, since shooting at 24fps usually means a pretty slow shutter speed of 1/48th of a second, and practically every scene in your film has motion blur baked right in. VFX artists know this, and add motion blur back in to make their sequences look natural. (This is one reason, incidentally, why 4K digital cameras have not made production still photographers obsolete: we need them to snap clean frames at much higher shutters speeds on set.)

But Trumbull rejected motion blur because the “stars” would have just become white streaks. Great if you’re making the jump to light speed, not so great for anything else. The same is true again for end credits. Blurred text is just that—blurred. And illegible.

Another approach is to reduce the contrast. 2012’s Young & Wild is one example of an unconventional scrolling color palette. (Heads up: very NFSW, skip to 3:14 for the scroll.)

But the reality is that most films are going to opt for the classic, monochrome color scheme.

Higher frame rates certainly make for a smoother scroll. Which is fine for video games, and not much else. Trumbull’s observations in 1968 formed an early basis for his later work advocating higher frame rates, but theatrical exhibition today is still 24p for any movie not about Hobbits.

The last option is to just slow it down. Which is exactly what Trumbull and Kubrick did: slow, slow pans across starry void of space. (This might also help explain why 2001 is, what, nine hours long?) Like Mr. Trumbull, we have found that the basis for gorgeous end titles is a slower scroll. If you’re rolling your own, you want to aim for 3 pixels per frame (in 2K or HD). That’s the sweet spot. 4 is fine. 5 is pushing it. 2 feels very, very slow. It’s that simple.

Except, of course, that it’s not. If your scroll is slow, it gets harder to hit an acceptable target duration. So you’ll then need to typeset creatively in order have your full list of credits add up acceptable length. (That’s challenging to do once, let alone after the 100th revision.)

The complexity and time-drain of making scrolling credits sequences (that don’t suck) lead us to create our web-based tool Endcrawl, which you should absolutely check out, since it sweats all of those little details for you. But if you’re doing it by hand, I hope some of this helps.

Of course speed isn’t the only factor to getting an end titles sequence ready for prime time. You have to select your fonts with care, and above all, avoid sub-pixel motion. In the immortal words of Michael Ende: this is another story and shall be told another time.

I’m extremely shocked and grateful that Mr. Trumbull gave me the time of day, and graciously corresponded about frame rates, star fields, and (yes) end titles.

Hey, while you're here ...

We wanted you to know that The End Run is published by Endcrawl.com.

Endcrawl is that thing everybody uses to make their end credits. Productions like Moonlight, Hereditary, Tiger King, Hamilton—and 1,000s of others.

If you're a filmmaker with a funded project, you can request a demo project right here.