Why the RED Camera was (and was not) a Disruptive Innovation

Photo courtesy Offhollywood

I had the first two RED One (and Epic) cameras. They had a huge impact on production tech, but less so on the film industry as a whole. Here's why.

NAB, you’re wearing pretty thin.

Let’s start with the expo floor, which always feels like an extension to the mandatory acres of jangly casino floor we’re routed through on our way there. The one-armed bandits and vendor booths both vie for attention. Each year we’re on the hunt for something new and game-changing. And each year instead we are proffered incremental improvements to small, tactical annoyances. Surprises are rare.

The World Of Atoms moves at its own lumbering pace, and neither the slot machines nor the display booths change much from one year to the next.

Set against the World Of Bits—where new soft technologies can mutate and disperse in just days and weeks—digital cinema sure feels like new skin for some very old wine.

The RED Camera was a rare exception to this slog. Affordable 4k and native RAW workflows were distant sci-fi when rumors started swirling in 2005. But just two years later, RED was shipping cameras to its first customers.

Full disclosure: I was one of those customers.

Over Labor Day weekend 2007, I became the co-owner of the first two production model RED One cameras. (For the record: serials #0006 and #0007. The first five belong to RED founder Jim Jannard’s private collection.)

I would spend the next five years putting the system through its paces, running native 4k RAW pipelines on scores of projects. That path would start with the earliest RED indies you’ve never heard of, and lead through Academy Award winners like Beginners and The Great Gatsby.

And in case you missed the headline: I do not think that the RED camera was a disruptive innovation.

But before the flaming arrows of fanboys darken my skies, and I’m banned from RedUser for all eternity, please allow me to explain.

Photo by Adam Dachis / CC BY. Cropped, hacked & retouched.

Will Lobstermania 2 resolve all the lingering questions left from Lobstermania 1?

The Disruption Troika

We filmmakers abuse the term “disruption” liberally, but then so does Silicon Valley. The authors of classic Disruption Theory recently took to the Harvard Business Review to try and set the record straight. And rightly so: disruption doesn’t simply mean “shiny new toy” or “this will make my day job harder.”

But a worthy idea will also assume a life of its own, so I hope Clayton Christensen will forgive my occasional breach from his canon.

A Disruptive Innovation is three things:

- It is Inferior. The new product or tech has deliberate, glaring omissions in its specifications or feature set. Conventional wisdom gazes upon these omissions in horror. Pearls are clutched. Monocles pop.

- It is Combinatorial. The innovation does not rely on radical new breakthroughs (think cold fusion, warp drive, or invisibility cloaks). Instead, it leverages readily available technologies and re-combines them in new ways.

- It is Bottoms-up. Disruptors identify an under-served market and start selling there. Over time, the disruptor’s product improves and is able to consume greater market share. The incumbents are either pushed out, or they end up balkanizing themselves into small, luxury pigeonholes.

Let’s look at a number of concrete examples, and see how RED stacks up.

Photo courtesy Offhollywood

Pictured in there somewhere: the author. First weekend out with REDs #0006 and #0007.

I. Disruption is Inferior

Inferior doesn’t mean cheap or low-tech: an “inferior” disruptive product can have a high ticket price. We’re not talking about manufacturing defects or other quality control issues like the iPhone 4 antenna debacle, either.

A disruptive product deliberately ships with specs that appear subpar to conventional wisdom.

A. Inferior Steam Shovels

My five-year-old could tell you that earth movers are hydraulic. But in the early twentieth century, everything was cable-operated.

And only occasionally would a cable snap and maybe decapitate you.

Hydraulics entered that market underpowered and niche: it would take years for the technology to match the brawn of cable-operated machinery. So instead of going head-to-head with the heavy iron, disruptive diggers introduced lower-power models that were only good for small jobs.

These new hydraulic excavators were inferior by traditional measures like shovel size and extension distance. But all new homes need trenches dug for water and sewage lines. And that used to be done with shovels. By hand. In the post-WWII housing boom, new hydraulic backhoes took over the job. They even turned an emphasis on narrower shovels and maneuverability into an advantage.

As hydraulic technology improved over time, it consumed more and more market share. In a move history would see repeated many times later, the incumbent firms eventually tried to make the switch to hydraulics as well—buy they waited until it was safe. By then, the disruptors had accumulated a massive head start. The incumbents were largely pushed out of their core markets.

B. Inferior iPhone

Apple’s iPhone strategy was heavily influenced by the disruption playbook. This is where I fork from Disruption Orthodoxy, since Clayton doesn’t think the iPhone fits the bill. But begging Clayton’s forgiveness, we tend to forget how the original iPhone showed any number of deficiencies compared to “real” smartphones at the time:

- No 3G support

- No Flash support

- No physical keyboard

- And let’s not forget that we didn’t even get copy & paste until iOS3.

Here’s former Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer clutching his pearls:

To this day, iPhones do not have the fastest processors or best cameras and lenses that smartphone money can buy. But while Steve Ballmer laughed, Apple was betting on a different set of tradeoffs. The iPhone’s launch is now widely recognized as the start of the third epoch of consumer computing.

C. Inferior Final Cut Pro X

I was at a fancy Angénieux soiree (at NAB, of course) five years ago when Final Cut Pro X was announced. We had all been waiting and hoping for a fresh 64-bit re-write of the creaky pro app. But Apple dropped a bomb that day.

So we all grabbed our iPhones, pulled up the Supermeet news feed, and snickered into our cocktails over:

- No EDL support

- No video output

- No multicam

- No native OMF support

- No backward compatibility

The iMovie Pro epithet was born about ten seconds later.

But while our monocles were busy popping, Apple was also introducing some less obvious innovations:

- Magnetic Timeline

- Live Scrubbing

- Facial Recognition

- Auditions

- Smart metadata keyword tagging instead of “bins” (an outdated 35mm film metaphor)

These may yet bring the NLE world kicking and screaming into the 21st century. And FCPX has continued to quietly innovate while the first several feature films have since been edited on the platform.

D. Inferior RED

The RED One looked and felt like a space-age ray gun. It turned heads and drew small crowds on the street. (This was 2007, people.) So do I dare call it inferior?

Well for starters, early firmware builds were rocking a font suspiciously close to Comic Sans:

I am not making this up.

Typographic faux pas aside, there were some bigger issues:

- Initially there was no viewfinder, only an LCD screen.

- The only signal out was 720p.

- The only supported aspect ratio was, bizarrely, 2.00:1.

- The first Redcode RAW codec had a fairly high compression ratio (about 12:1).

- The camera employed an FPGA, which runs hotter, hogs more real estate, and burns more power than an ASIC.

But the real flashpoint was RED’s choice of sensor. Everything more or less turned on this.

- First, RED went with a single-chip architecture. This generally requires de-mosaicing—a process that imposes a roughly 36% penalty on spatial resolution. In that sense, 3-chip architectures were considered technologically superior. Star Wars Episodes I-III were shot on SONY F-900 and F-950 cameras, which use 3 separate 2/3” sensors. [Update: @5tu notes that Star Wars I was shot on film. Episodes II-III were shot on SONY’s cameras.]

- CCD sensors are generally more light-sensitive and make it easier to implement a global shutter. RED chose less photosensitive CMOS sensors.

- CMOS sensors also have slower refresh rates, which meant that the camera would have rolling shutter issues. One solution might have been a mechanical shutter, considered superior since they behave more like film cameras and mostly get around vertical rolling-shutter problems. Hence we find mechanical shutters on cameras like the Thomson Viper, Dalsa Origin, Arri D20/21, and the SONY F65.

While camera manufacturers were far from monolithic, RED’s approach ran entirely orthogonal to prevailing engineering consensus: they built a single-chip, 35mm, rolling-shutter CMOS sensor camera—with all of the drawbacks listed above.

The first time you picked up an iPhone you didn’t care about its hardware specs: The UX was qualitatively in a different stratosphere. RED banked on a similar gamble: that all of those tradeoffs would pale when you started shooting with a 35mm sensor, PL mount, and RAW files. Because suddenly, your digital footage looked like A Real Movie.

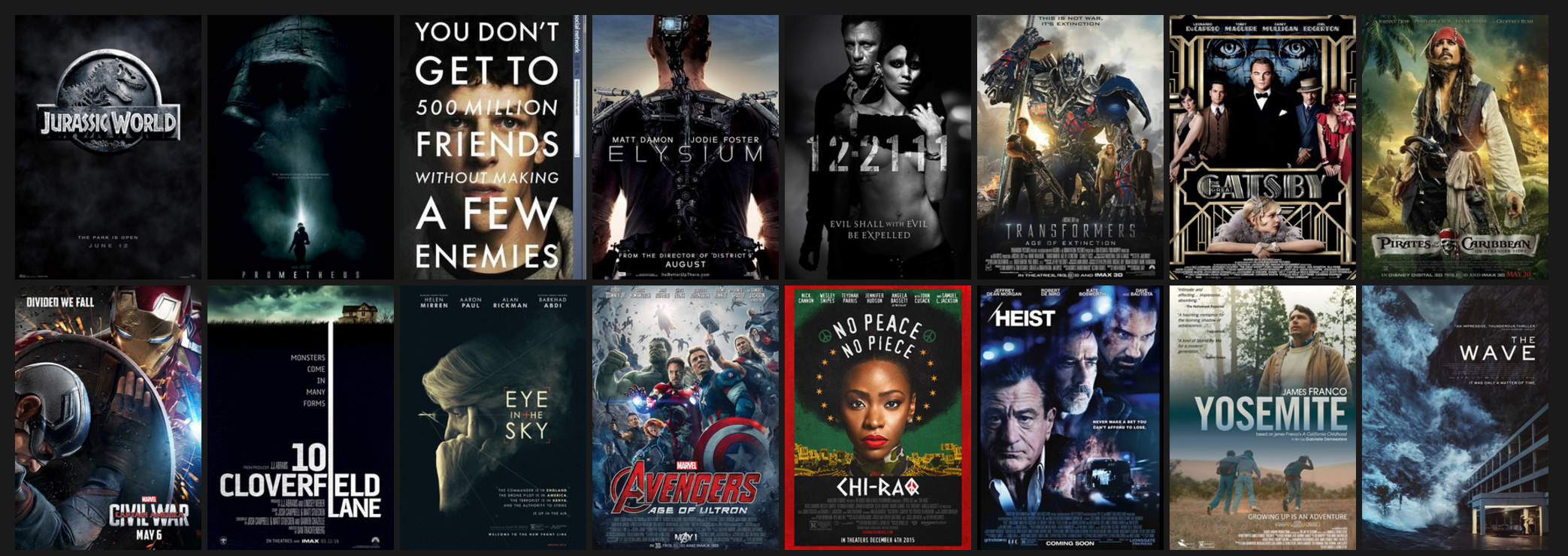

Pictured: A Real Movie.

Anyone who has ever tried to bolt PL mounts onto Varicams and DVX-100s remembers this hunt for the holy digital/cinematic grail. And RED had suddenly put it within reach.

Still, I still don’t think the RED Camera was disruptive. Let’s keep going.

II. Disruption is Combinatorial

All technological advance is built on prior knowledge. But the combinatorial aspect of Disruption Theory revolves around the key insight that you don’t need radical breakthroughs—like cold fusion or warp drive—in order to upend an entire industry. Instead, you need to find creative and unexpected new ways to re-combine available technologies.

Disruptive vs. Sustaining

Over time, hard drives have evolved along several axes, including density and size.

You and I expect our storage media to be constantly increasing in capacity. But Moore’s Law is not automatic: billions of R&D dollars have gone into making this a reality. Keeping the pace of consumer demand has required a number of expensive and “radical” innovations. In the hard disk industry, that meant moving gradually from ferrite-oxide heads to thin-film heads to magneto-resistive heads.

Those types of inventions emanate from large, established firms with armies of top engineering talent. But critically, these advancements don’t lead to new products or address new markets. Instead, expensive, “radical” technology breakthroughs usually serve to sustain existing products, along their existing trajectory, selling to an existing customer base.

Clayton identifies this a sustaining innovation. And he is at pains to distinguish sustaining from disruptive innovations. Disruption has very different hallmarks. In fact, most of the time you hear the word “disruptive” tossed about, the speaker is actually describing a sustaining innovation.

This simple insight is also one of his most profound. It’s one we ignore at our own risk.

A. Combinatorial Hard Drives

While making hard drives denser required a lot of expensive R&D, making them smaller was a different exercise. It was usually a matter of creative bricolage: re-combining available technology in novel ways.

This often started in large companies as well, but a similar pattern would emerge:

- Smart engineer at OldCo devises a smaller hard drive, using the existing technology stack.

- OldCo’s core customer base say “no thanks.” They want a faster horse.

- Company quietly kills product.

- Smart engineer exits, forms NewCo, and eventually eats OldCo’s lunch.

With the benefit of hindsight, the frequency of this verse-chorus-verse is startling. But ladder-climbing middle managers have short horizons, and they will gladly strangle your new idea if it’s not going to help the balance sheet next quarter. (Not that there’s anything wrong with this: that’s their job. You just need to understand this.)

Smaller hard drives were able to compete along new vectors like ruggedness, power consumption, and form factor. This meant selling to new and emerging markets that had different uses for the product. And frequently, those new markets would go on to dwarf the original market being disrupted. (For example, would you rather be in the consumer smartphone business or in “enterprise smartphone sales”?)

At a risk of over-simplifying: denser hard drives were sustaining and served the status quo, while smaller hard drives were disruptive and challenged the status quo.

And critically: while established players are almost always technologically capable of making disruptive products, they are almost never culturally able to bring them to market. The only way forward is to start a new company.

B. Combinatorial Google Docs

For years, Google Apps have been nipping at the heels of Microsoft Office products. (And under Satya Nadella, Microsoft has finally started responding.)

But Google didn’t need to invent any radical new technologies for products like Google Docs and Sheets. Instead they combined:

- The modern web stack, including HTML5, CSS3, JavaScript, and frameworks like jQuery

- Operational Transform techniques (aka a thing that lets different people edit a document at the same time without stuff blowing up)

- XMLHttpRequest (aka the thing that lets you refresh small portions of a web page without having to constantly reload the whole page, 1997-style)

Like many other companies with SaaS offerings, Google leveraged many existing and readily available technologies into unique new products. That leverage allows Google and startups alike to compete with traditional, on-premise software.

C. Combinatorial iPhone

The original iPhone is another great example of combining existing technologies into something new. Its core technologies included:

- Multi-touch: which, contrary to popular opinion, was not invented by Apple

- LED displays

- Wireless protocols like GSM and CDMA

- GPS

- WiFi

- Bluetooth

- JPEG, mp3, AAC, mpeg-4, and other compression techniques developed by an array of industry groups

Benedict Evans of a16z has a great piece on the HMS Dreadnaught — the world’s first modern battleship — which he describes in the following terms:

“it contained few things that were fundamentally new – most of the key features had been around for a while and considered elsewhere – but it was the first to put all of them together in one place in the right way.”

I don’t know a better way to sum up the combinatorial aspect of disruptive innovations.

D. Combinatorial RED

Let’s look at some key highlights of RED’s technology stack:

- CMOS sensor – not invented by RED

- Super 35mm Format – not invented by RED

- PL Mount – not invented by RED

- Bayer Pattern – not invented by RED

- Camera RAW format — not invented by RED

- Wavelet Compression — not invented by RED

I’ve found that disruptive innovations often contain two killer apps: one obvious, and one hidden. In the case of RED, 4k was front and center. But the RED camera didn’t succeed because of a sensor with more photosites. People already knew how to make those.

The less obvious but far more important killer app was Redcode RAW: the idea of applying wavelet-like compression to an image before it was de-mosaiced. This is a perfect example of combinatorial innovation. And even the occasional grumpy CML commenter will concede that this was not a terrible idea. RED’s combinatorial play looked like this:

- Combining more photosites with onboard RAW recording;

- applying wavelet-like compression to RAW images;

- using an affordable single-chip 35mm sensor; and

- integrating this into an architecture that interfaced with cinema glass. (See above: Looks Like A Real Movie.)

RED opted for a very different set of trade-offs than what the incumbents deemed “correct”. (If you don’t believe me, I invite you to re-live this classic.)

RED’s trade-offs were themselves based on a very different set of assumptions about the future. As with the HMS Dreadnaught, RED was the first to pull all of these features together in that particular way.

Side note: all major digital cinema cameras today use single-chip CMOS architectures.

Yes, I am describing an almost classically disruptive play.

No, I still think the RED was not disruptive. Read on.

III. Disruption is Bottoms-up

Disruptors win by identifying emerging, under-served markets. For example, when 11” hard drive platters ruled the mainframe landscape, no one imagined that one day 1.8” hard drives would be embedded in iPods, pacemakers, or auto navigation systems.

Middle managers are incentivized to prioritize their careers around high-value, high-prestige customers. (The ones who have deep pockets, but keep asking for more of the same.) By comparison, emerging markets are difficult to measure and are initially lower-prestige. That’s central to the “Innovator’s Dilemma.”

A. Bottoms-up Motorbikes

Honda originally tried to compete with Harley-Davidson in the U.S. motorcycle market. Let’s just say that didn’t go so well at first.

Harleys were big, powerful, and to this day carry a brand image that no one else can touch. But something funny happened one day while Honda reps were tearing ass around the desert on their lightweight dirt bikes. It occurred to them that there just might be “an undeveloped off-the-road recreational motorbike market in North America.”

50cc Super Cubs were low-prestige compared to the heavy-iron Harley-Davidson market. So it took a long time for Honda to stop trying to compete with Harley head-on. But once they did, they were able to discover entirely new markets and establish a beachhead in the United States.

Only after they found their down-market groove was Honda in a position to move into adjacent markets. Like the heavy-iron Bike Week crowd. But they were eventually so successful in this that they pushed out most of the established competitors—except for Harley-Davidson (and BMW).

B. Bottoms-up Color Correctors

When Moore’s Law started to catch up with color grading, things got interesting.

Up until then, you needed heavy-iron systems. Then almost overnight, a new crop of GPU-accelerated color tools started to drop.

They were software-only, but we already knew how to build the hardware around this new generation of finishing systems. We had been building over-clocked, water-cooled, monster-GPU systems for years. The only difference: instead of trying to bump up our frame rates in Quake and Half-Life, we were now doing the same thing for Scratch, Speedgrade, and Final Touch.

Let’s do this.

This was orders of magnitude better than the old 3-way filter in Final Cut 4.5—and we finished feature films that way too—but early tools like Final Touch HD still clattered along at a Chaplin-esque 16-18 frames per second.

That wasn’t good enough for everyone. So the big-box post houses stuck with safer tape-to-tape and photochemical options for much longer. But guerrilla boutiques jumped into the file-based world with both feet. My colleague Michael Cioni even finished studio features like The Garfield Movie in Final Touch, years before Apple acquired them and re-christened the tool Apple Color.

These software makers had identified another under-served market: indie filmmakers and post professionals who wanted their footage to have a professional finish. (Another important component of “Looks Like A Real Movie.”) Up until then, color grading was still a dark art, carefully shrouded from the masses. That changed almost overnight.

This particular story has an interesting twist, because an erstwhile heavy-iron incumbent is once again the dominant player today. But it took an acquisition, re-brand, and flip to freemium software-only model to make this happen. That’s another story for another time.

C. Bottoms-up iPhone

On the day Steve Jobs announced the iPhone, the cool kids were rocking Blackberries and Treos. Because the smartphone was a business machine. More to the point—and I cannot stress this enough—in 2007, everybody hated their phone. This was axiomatic and as inevitable as death and taxes.

I have no interest in re-litigating the iPhone/disruption debate (again, I am in the minority here). But Apple rather deftly identified the under-served market: consumers who hated their mobile phones. In other words: everybody. Hiding right there in plain sight.

You might not be shocked that the major phone manufacturers dismissed Apple’s iPhone as an expensive toy. Let’s hear from Ballmer one more time:

Oops, sorry about that—I was thinking of this one:

When is the last time your company issued you a Blackberry, or any phone for that matter? While RIM and Microsoft worried about what business customers would think, Apple made an end run around the whole concept and introduced the world’s first truly viable consumer smartphone. To the extent that enterprise is interesting to Apple at all, it is now dwarfed by the consumer smartphone market.

D. Bottoms-up Everything

What are the chances that FCPX is the NLE equivalent of a 50cc Super Sub having a blast, while we True Pros once more lumber off to Bike Week NAB in our proverbial leather vests and ponytails? Inkjet printers sold downmarket of laserjet printers. Mini-mills initially sold lower-grade steel for washing machines instead of high rise beams. And hydraulic shovels started, literally, in the trenches.

The problems with selling down-market are well-documented: it is difficult to measure emerging markets because they don’t exist yet. Muscle memory and the desire for prestige and social capital incentivizes managers to keep selling to their “best” customers, not those down-market schlubs.

Time and again—and pace all of those corporate consultants peddling self-disruption workshops—there seems to be only one real way to pull off bottoms-up disruption: Start A New Company.

E. Bottoms-up RED

Which brings us back to the RED. I’d like to pause here and show you two pictures. Here’s the first:

Does Ghetto Dawg 2 resolve all of the lingering questions from Ghetto Dawg 1?

Not long before my company took delivery of RED Ones #6 and #7, I was producing the DI on this little movie. As much as I’d love to tell you about the cool guerilla post production we were pulling off at the time—and we were!—I don’t think anyone will argue that RED went downmarket when they sold their first two cameras to us.

Here’s the second picture:

I pulled this meme off one of the various online film tech cabals that I like to haunt.

Oh yes, how the True Pros love to hate on RedUser. It’s easy: the online community looks like it’s overpopulated by rank amateurs making rookie mistakes and asking endless dumb questions.

And very frequently, it is.

Would you like to know how to get ahead in life? You start as a rank amateur, make a bunch of rookie mistakes, and ask a ton of dumb questions.

But that doesn’t always sit well with the rank and file. A tenacious view still persists that most sacred Big Boy tools of the trade are rightly designated to priestly greybeards. The uninitiated are not yet worthy: their path must be traditional credentialism, trade organization membership, and years of apprenticeship-fealty.

RED took a very different view: put those tools directly into the hands of as many people as possible. (If your monocles are still popping at this point, may I perhaps recommend this product?) They did this through aggressive pricing, sure. But they also very deliberately fostered a global online community with a spectrum of seasoned veterans, aspiring semi-pros, and the previously-mentioned fanboy amateurs.

And tellingly, they created this community almost a year before the first cameras shipped.

The casual observer might also note that the person responsible for creating and growing this online RED community has since been promoted to President of RED Digital Cinema. Jarred Land has many talents, but I would not overlook his role in creating RedUser or dismiss it as tangential. From where I’m standing, his work was absolutely crucial to RED’s strategy and long-term success.

Where did this all lead? I’ve tried figure out how many RED cameras are on the street, globally. It’s not an easy task, and RED sure isn’t telling. But I asked Jarred, who approved the following quote for this article:

“Lots.”

– Jarred Land, President, RED Digital Cinema

My napkin math says the low-end number is 20,000. Don’t hold me to that; the numbers are a bit hand-wavey. It could easily be more than twice that.

Earlier I mentioned the Sony F-900 camera. Around the time our first REDs were shipping, there there were about two hundred of those in existence. In other words: RED took a paradigm of limited luxury models parked at high-end rental shops—and they 100x’ed it.

That’s pretty impressive. Especially in the World Of Atoms.

Do major camera houses still stock RED cameras? Of course they do. Are RED cameras used on major studio features?

Sure.

But does the bulk of RED’s revenue come from their high-end “enterprise” customers, or the down-market semi-pros? Jarred’s not telling. But I can wager a pretty good guess.

Photo courtesy Offhollywood

So was the RED Camera a Disruptive Innovation?

Which brings us full circle, and back to those flaming fanboy arrows currently suspended in mid-air above my head. Was the RED camera a disruptive innovation?

Let’s tally:

- The RED One was initially “inferior” along many traditional vectors.

- The RED One was a fascinating combinatorial play, similar to the iPhone or the HMS Dreadnaught

- RED Digital Cinema very deliberately sells to everyone—not just to the Great Big High School In The Sky.

If I ignore the miniature Clayton Christensen sitting on my shoulder, splitting hairs on the finer points: yes, RED Digital Cinema pulled off a near-textbook execution of the disruption playbook. If he publishes a third edition of The Innovator’s Dilemma, Clayton should consider adding a RED case study.

But RED camera was, is, and always will be—a camera.

Hands up if you work in the camera industry.

Chances are, if you’re still reading this, you consider yourself a filmmaker. You work in the film industry. Whether your on your 11th straight hour of roto, or 11th Red Vine from the craft services table. You’re in the business of making films.

In no way will a RED camera, or any other piece of tech you find on the convention floor change:

- how films are “packaged” and financed;

- what groups of people have realistic access to funding;

- the massive waterfall modes that still dominate production;

- the types of films that are accepted into major festivals like Venice, Toronto, Berlin, and Sundance;

- what kinds of stories get told in the first place;

- who gets to tell them; and

- for whose benefit.

In fairness, no one in those vendor booths will claim otherwise. It is we filmmakers who are constantly losing that script.

We love to throw around words like “disruption” while perusing a buzzing expo that, for all of the technical prowess on display, is ultimately one of the planet’s single greatest assemblies of sustaining innovation theater.

Better Questions

Ask yourself:

- Are HBO NOW, STARZ, Playstation Vue, Xfinity, and other Over The Top offerings disruptive? Or are they sustaining innovations selling the same product to the same customer base?

- Are Virtual Reality and High Dynamic Range examples of disruptive tech? Or do they primarily sustain established companies like Dolby, Sony, or Facebook?

- Stereoscopic 3D, 4k/8k, Wide Color Gamut, Auro, IMAX, ATMOS, Barco Escape: same question?

That’s a good place to start, since we are so often guilty of conflating what is sustaining and what is disruptive.

Love them or hate them, RED thoroughly disrupted the camera industry. And we should all be eternally grateful. You wouldn’t have your ALEXA and F55 today if not for Jim Jannard.

But we then picked up those cameras and made the same things we always had: two-hour features, 30/60-minute TV shows, and 30-second commercials.

If we want to go further than that, we need a fresh set of questions. I could write another 100,000 words on that topic. And probably will.

But let’s just start here: What does a disruptive piece of content look like?

Deanan DaSilva, Evan Schechtmann, Michael Cioni, Graeme Nattress, Mark Pederson, Gus Sacks, Eric Camp, Jeffrey Hagerman, and Tom Wong contributed to this article.

Hey, while you're here ...

We wanted you to know that The End Run is published by Endcrawl.com.

Endcrawl is that thing everybody uses to make their end credits. Productions like Moonlight, Hereditary, Tiger King, Hamilton—and 1,000s of others.

If you're a filmmaker with a funded project, you can request a demo project right here.

How to crush a job interview with us

I had the first two RED One (and Epic) cameras. They were many things, but not...