Content Is Not King

Or: if Content is King, why do Dumb Pipes keep buying up studios?

“Content is king.”

Or so filmmakers love to intone, reciting the phrase like a proverb or catechism.

Below the line, we are especially fond of this truism. And small wonder: whether you’re an editor, VFX artist, or DIT, you have a front-row seat to the spectacle of other people realizing their personal creative visions. You might be toiling on that spec script. Or working your way up a particular department chain. (Or both.)

Meanwhile, you those content producers hire you, work you to the bone, and occasionally yell at you a lot. They wear neat blazers to festival premieres and post the red carpet pics to their IMDb profiles. And of course they own all of the upside.

From your foxhole, content sure looks like, if not exactly king, then at very least boss.

Of course, all that upside is worth precisely nothing 99.999% of the time. One week you’re mugging with Robert Redford at the Sundance Directors’ Brunch, the next you’re wondering how to cover this month’s rent.

If content is “king,” it’s only king for a day.

But this notion—that content creators hold all of the cards in the show business economy—is still a powerful one. It’s just not borne out by reality.

@MatthewACherry each year I get jelly of my friends with movies in Sundance. Right up until April, when they call me looking for a job.

— Pliny (@iampliny) April 29, 2016

1. If Content is king, then why are telecoms buying up studios?

Sprint just announced its plans to purchase a 33% stake in Tidal, the renowned-but-perpetually-troubled music startup. This falls in line with a running trend I never tire of pointing out:

- Comcast acquired NBC Universal

- AT&T is acquiring Time Warner

- Verizon acquired AOL and is acquiring Yahoo!

- Sprint is acquiring a major stake in Tidal

(Full disclosure: I am currently employed by HBO, and here’s a big old disclaimer about that.)

In each case, it’s a telecom—those much-maligned “dumb pipes” with regional monopolies and infuriating customer service—that are doing the buying. If content is king, shouldn’t it be the other way around?

2. Content is volatile.

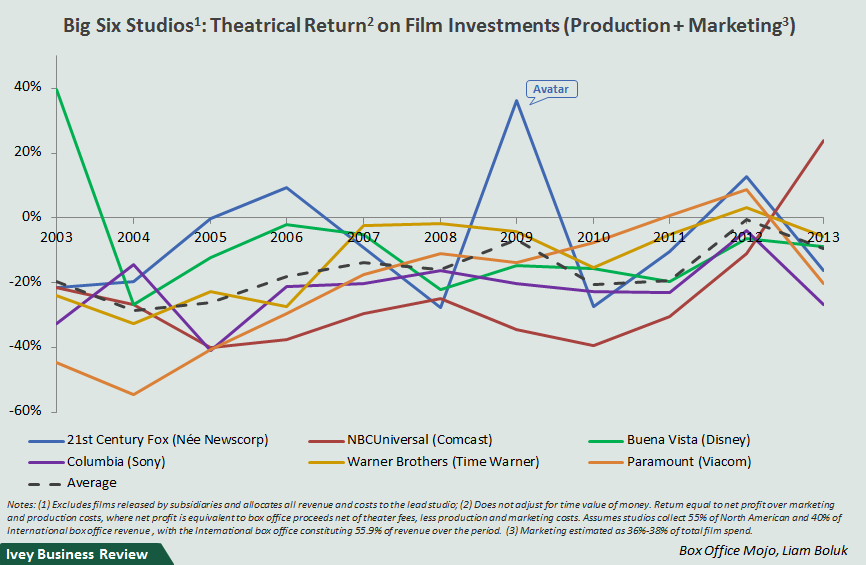

In 2013, REDEF’s Matthew Ball published his quintessential “The Future Of Film” series. One of his most important observations lives in this chart:

The key takeaway here is not the large surface area below the waterline. (Although that is troubling enough in itself.)

The key takeway is the high volatility on display here. These numbers are essentially a random distribution.

Predicting taste is a notoriously difficult undertaking. Although the media business is frequently compared to tech, the more apt comparison might be the restaurant business. (Which the New Yorker once called a “taste-predicting nobody-knows-anything businesses like Hollywood”. Just so.)

This volatility used to be mitigated by two factors: geographic monopolies, and scarcity. The internet has eradicated the former. As to scarcity: well, more TV shows were cancelled in 2014 than aired just 15 years earlier.

This new reality has put traditional studios, networks, and publishers in a bind. On the one hand, individual content creators are learning they do quite well on their own, leveraging low production costs and cheap distribution. Examples here include Louis CK, Casey Neistat, or the for-pay Stratechery blog.

On the other hand, we have entities who are able to aggregate on a massive scale: think Netflix or Facebook.

Everyone else finds themselves in a 21st-century twist on the “middle class squeeze.” Too large to leverage digital efficiencies, but too small to offer a comprehensive entertainment package, traditional studios are left lurching about for new monetization strategies.

3. Attention is zero-sum.

“Content,” broadly defined, places high demands on our attention.

And “content” has already seeped into most cracks in our personal lives, from TV shows consumed during your commute to that quick Twitter feed-swipe in the elevator. Few frontiers remain. There is no Third or Fourth Screen.

Publishing, video games, or television—one of these is necessarily consumed at the expense of the other. These are are no longer growth industries; they are merely engaged in a zero-sum competition for a finite resource.

By contrast, many other types of “subscription” products are consumed passively. Auto insurance, home security systems, or water and electric all run in the background. They only occasionally require our passing notice. Mobile and broadband access fall into this category as well. Many of the zeroes and ones that we purchase are consumed passively. As long as we keep demanding higher data allowances, faster speeds, and greater coverage, there is no clear ceiling to this industry’s growth.

Telecoms might proffer “dumb pipes,” but those dumb pipes have a lot of room to grow.

4. Connectivity is King

A detailed critique of the “Content Is King” aphorism emerged back in 2001 when Andrew Odlyzko—an AT&T employee, no less—published an elaborate, 10,000-word analysis in First Monday. Bill Gates thought that the Internet’s killer app would be content. Odlyzko disagreed, arguing that the killer app instead was communication:

connectivity is more important than content. The evidence is based on current and historical spending figures. I also show that the current preoccupation with content by decision makers is not new, as similar attitudes have been common in the past.

Odlyzko’s analysis is still worth reading today. But if you’ve ever hemmed and hawed over a $7.99 Hulu subscription but gladly pay your $100+ mobile bill every month, you’ve likely proven him correct.

5. Nobody wants to pay for content any more.

There is a secular trend toward the commoditization of all content. Notice that today, Time Warner consists of:

- Warner Brothers (a movie studio)

- Turner (a cable network)

- HBO (a little bit of both)

But the last time Time Warner went through a merger, it also owned a publishing arm (TIME, Inc.) and various record labels (Warner Music Group). Both have long since been spun off. The trend is a straightforward as it is worrying: people don’t like to pay for content, and we’re gradually moving along a Moore’s-Law curve of what people won’t pay for:

- first journalism, whose output is measured in kilobytes;

- then music, whose files are megabytes;

- now TV shows and movies, which are measured in gigabytes.

In this landscape, content stops being a viable business model in and of itself. Instead, entertainment media is relegated to an add-on feature, providing “stickiness” to other, more profitable, platforms. Amazon Prime is the best example of where this is all headed: not content as a business, but Content-as-a-Feature.

Content isn't king. Connectivity is.

Sprint 💰 Tidal (33%)

Comcast 💰 NBCUni

Verizon 💰 Yahoo, AOL

AT&T 💰 Time-Warnerhttps://t.co/77I2sWaPvX— Pliny (@iampliny) January 23, 2017

Hey, while you're here ...

We wanted you to know that The End Run is published by Endcrawl.com.

Endcrawl is that thing everybody uses to make their end credits. Productions like Moonlight, Hereditary, Tiger King, Hamilton—and 1,000s of others.

If you're a filmmaker with a funded project, you can request a demo project right here.

Revolutions Always Come In Twos

Or: if Content is King, why do Dumb Pipes keep buying up studios?