Don Coscarelli: True Indie

True Indie

What makes a filmmaker truly independent?

Writer, filmmaker, and producer Don Coscarelli spent the last forty years carving a path through the heart of genre cinema, averaging roughly one entry in the Phantasm franchise per decade, with stops along the way to tame some beasts (1982’s The Beastmaster), track Lance Henriksen through the deep wilderness (1988’s Survival Quest), witness an elderly Elvis Presley and JFK fight a mummy (2002’s Bubba Ho-Tep), and follow two bumbling burnouts to the end of the world (2012’s John Dies at the End). [Ed. Note: The Coscarelli-produced Phantasm: Ravager used Endcrawl, which publishes this site.]

A Personal World

In 2018, Coscarelli published his memoir True Indie: Life and Death in Filmmaking, a feast of anecdotes, wisdom, and contemplation from almost half a century of filmmaking experience. Ask anyone who’s met the man and they’ll tell you that Coscarelli is warm, welcoming, and happy to talk movies and rub elbows with fans new and old. It seems his approach to writing a book is very much the same — reading True Indie feels like someone you’ve known for years casually tell you about the time they set themselves on fire while blasting a shotgun from the trunk of a moving car.

The first few chapters of True Indie follow Coscarelli and his childhood friends around his hometown of Long Beach, California. Their neighborhood hijinks include stealing wood to make a boat, riding bikes around town, building a world of their own. It’s easy for the reader to put themselves in the shoes of these characters, and it’s no surprise to learn that these early years established a framework for everything Coscarelli has done as a filmmaker.

“Movies and television are all about world-building,” he writes in an email interview with The End Run. “That’s why it’s so fun. Orson Welles once said a movie is like the greatest electric train set a kid could ever have. It’s all about building that train set, creating the characters and how they interact with one another. What they wear, what they drive, what kinds of weapons they use when things get out of control. It’s better to worry about someone else’s reality instead of your own.”

A 19-year-old Coscarelli produced his first feature film in 1975 — Jim, the World’s Greatest. It was there that he met Angus Scrimm, who would go on to play a crepuscular undertaker in Coscarelli’s 1979 breakout-hit Phantasm — a modest fantasy-horror film which has since found a place in the cultural lexicon of American independent cinema precisely because of its everyday setting, and the way its ordinary characters honestly respond to the story’s extraordinary circumstances. When the film’s teenaged protagonist Mike (Michael Baldwin) spies an elderly undertaker — Scrimm’s “Tall Man” — tossing a casket around like a hacky sack, one can’t help but silently mouth “What the fuck?” along with him. This is two towns over from you, this is the cemetery that you hold your breath while walking past. It’s small and believable, and that’s why it’s scary. If something like this can happen in a podunk town like that — what could the rest of the world contain?

Phantasm’s small-town scale was a matter of necessity, says Coscarelli. “The idea of bringing in police or military forces was just beyond anything we could possibly accomplish,” he remarks. “Early on I made the decision to limit the number of protagonists and set the story in a depopulated section of Eastern Oregon. This worked to our favor, as the setting was stark and lonely, and the final confrontation between our three heroes and the Tall Man was very personal.”

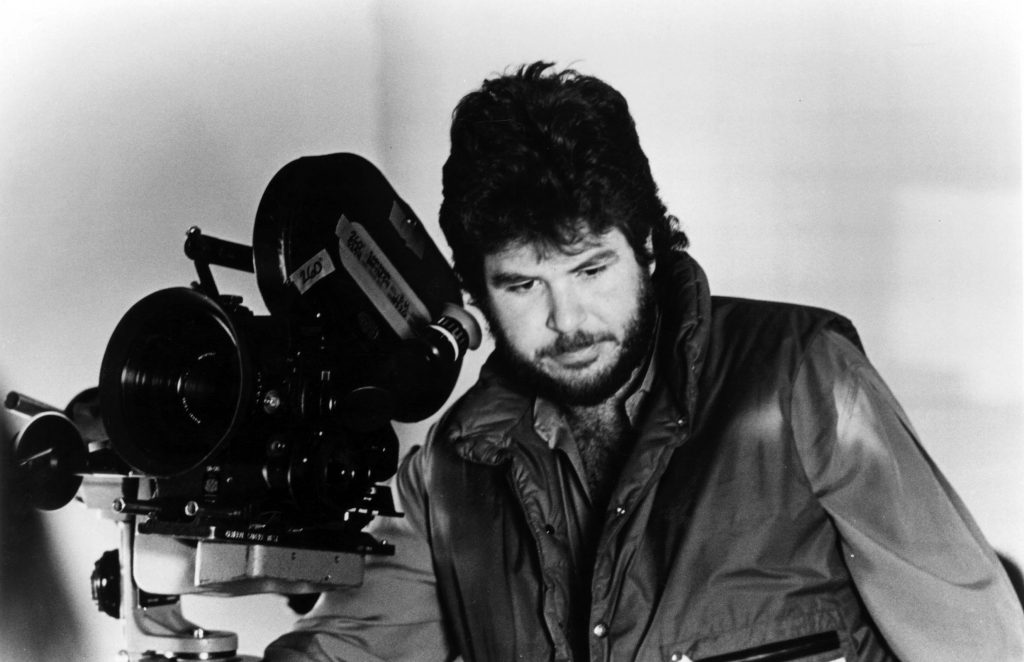

Coscarelli on set, from a lobby card for 1988’s Phantasm II.

If there’s two things that Hollywood is not, it’s small and personal, and Coscarelli would learn this the hard way. After two difficult years of production on the sword-and-sorcery epic Beastmaster, the young director was brought to New York for a meeting with legendary producer Dino De Laurentiis, who offered him an opportunity to direct a sequel to John Milius’s Conan the Barbarian, which also came out in 1982.

Coscarelli weighed his options: “My next project would involve months in another country, filming another muscle-bound hero in a loincloth for another strong-willed international producer for whom English was a second language… Just my luck.” He decided to pass, and it would be years before he’d make another film. “I’d be lying if I told you I never second-guessed that decision,” he reflects.

Three years later Hollywood came calling again — again De Laurentiis — this time with a tempting offer: a deal for multiple works by Stephen King. Without even knowing which one it was, Coscarelli jumped at the chance, which turned turned out to be the adaptation of a collaboration between King and horror/fantasy illustrator Bernie Wrightson, a short horror novel called Cycle of the Werewolf.

This too ended up a bust, but the story is worth it, from creative differences (Coscarelli wanted to save the monster’s reveal until later in the film; De Laurentiis demanded it be shown in the beginning), across language barriers (De Laurentiis had everything written for the film translated into Italian), to the creative process (the werewolf was to be an animatronic monster created by Carlo Rambaldi, who made the 35-foot King Kong for De Laurentiis’s 1976 remake), the chapter culminates with the producer throwing all of the notes Coscarelli wrote with King into the trash. Coscarelli’s lone contribution to the final product is its title: Silver Bullet.

A Personal Story

Coscarelli understands that there’s no point in telling a story — whether it’s a film or a book — unless an idea is conveyed, and when one considers the overarching themes of his films, a clear idea is formed: you don’t get to the end alone. You’ll need the help of your family and your friends to survive, whether it’s battling the forces of darkness or a contentious producer (or both). This is the essence of True Indie: when you’re truly independent, the only people you can really count on are the people closest to you. Don’t give up, work hard, and work together. It’s the difference between life and death.

Hey, while you're here ...

We wanted you to know that The End Run is published by Endcrawl.com.

Endcrawl is that thing everybody uses to make their end credits. Productions like Moonlight, Hereditary, Tiger King, Hamilton—and 1,000s of others.

If you're a filmmaker with a funded project, you can request a demo project right here.

A Brief History of Interactive Film

What makes a filmmaker truly independent?