Safety Last! / Public Domain

Why Film has not been Disrupted (Yet), Part 3

Moore's Law may be gradually catching up with filmmaking, but it's our own mental habits that will prove harder to budge.

This entry is part 3 in a series examining why the film industry has resisted disruption so far:

- Making a movie is still an all-or-nothing proposition.

- Film technologists are focusing on all the wrong areas.

- Filmmaking is (computationally) expensive.

- We are a deeply traditional, conservative, and sentimental lot.

- The film industry neutralizes its best and brightest.

- Postscript: There Are Always Two Revolutions

3. Filmmaking is (computationally) expensive.

Filmed entertainment is expensive. Not just in terms of dollars: it’s computationally expensive as well. This simple reality has placed many obstacles in the ways that we conceive of and produce movies and television.

Venkatesh Rao has written at length about the “mass flourishing” made possible by distributed, open collaboration in the software world. So much code today is shared, forked, and redistributed that it’s virtually unthinkable to create a piece of software from scratch today. Filmmakers, meanwhile, are perpetually re-inventing the wheel.

If you’ve ever installed a game on Steam, you know exactly what I’m talking about.

Rao argues that this trend gradually moving into all other arenas. (Also known as “software eating the world”). And he’s right. For a better introduction, I highly recommend two essays: Getting Reoriented and Rough Consensus and Maximal Interestingness.

But computer code always had one large advantage: it generally consists of small, lightweight text files that are easy to share and distribute. And that was the case decades ago, even when ancient dial-up modems still used terms like baud.

The primitives of filmmaking, other other hand, are of a different sort: bulky binary files weighing in at megabytes per frame, tens or hundreds of megabytes per second. Indie films routinely generate tens of terabytes of data. Our raw materials are orders of magnitude larger those from other fields like journalism, software, or music. And unlike text files, these cannot be easily diffed and forked.

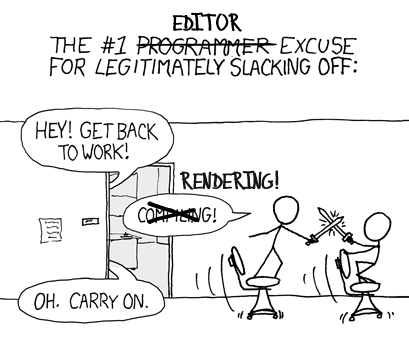

Likewise, the computational expense is significant. Compiling your code might take a while, you don’t know true pain until you’ve had to run several grain reduction passes on a 16mm film.

With sincere apologies to Randall Munroe.

So we find multiple, overlapping factors that have helped keep disruption at bay:

- First, digital images have large data footprints and are computationally expensive to manipulate.

- Second, the larger file sizes make it more difficult to transmit our “primitives” (frames of video) across networks like the Internet.

- Third, our primitives are binary files, which behave very differently than text files.

- Finally, we have always been taught that we must toil away hidden for years, and only release our work from its quarantined state once it is Perfect and Complete.

The first three factors on that list continuously re-enforce the fourth. Over time, those simple technological obstacles have hardened into a grab bag of bad habits. Production characterized by Waterfall, isolation, and all-or-nothing dynamics are not serving us well—either creatively or in business.

But there are glimmers. Some filmmakers are thinking about how to move beyond Waterfall storytelling.

- Open Source films on platforms like Blender are an excellent place to start.

- Some nice folks in Melbourne are experimenting with “Lean Filmmaking“.

- The recently released Adam demo short film (rendered in real time with the Unity Engine) has a number of implications beyond the obvious.

In many fields, whole generations of makers have cut their teeth in environments of open sharing and bricolage. Not so in film. This reality is all the more startling when we consider how truly collaborative filmmaking is (or is supposed to be).

Moore’s Law may be gradually catching up with filmmaking. It’s our own mental habits that will prove harder to budge.

Hey, while you're here ...

We wanted you to know that The End Run is published by Endcrawl.com.

Endcrawl is that thing everybody uses to make their end credits. Productions like Moonlight, Hereditary, Tiger King, Hamilton—and 1,000s of others.

If you're a filmmaker with a funded project, you can request a demo project right here.

Why Film has not been Disrupted (Yet), Part 2

Moore's Law may be gradually catching up with filmmaking, but it's our own mental...