Safety Last! / Public Domain

Why Film has not been Disrupted (Yet), Part 4

We show too much deference toward the film industry's old guard. It's time to lose that love affair.

This entry is part 4 in a series examining why the film industry has resisted disruption so far:

- Making a movie is still an all-or-nothing proposition.

- Film technologists are focusing on all the wrong areas.

- Filmmaking is (computationally) expensive.

- We are a deeply traditional, conservative, and sentimental lot.

- The film industry neutralizes its best and brightest.

- Postscript: There Are Always Two Revolutions

4. We are a deeply traditional, conservative, and sentimental lot.

You didn’t start working in film and TV because of a jobs fair, or because your father’s business partner pulled you aside at a dinner party for a moment of sage economic advice.

“I want to say one word to you. Just one word. Are you listening? Celluloid.”

At some point in our lives, we were all profoundly moved by something that we saw on the screen. The emotions imprinted are a Deep Magic that we carry around with us. We retain profound spiritual and endocrinological connections with them. They define us. In fact, some of our careers might be best understood as a series of attempts at re-creating them.

But this very love has also imbued us with unhealthy levels of reverence toward the old systems—the ones that produced those works that inspired us in the first place.

So we find, for example, that there are far more websites, books, and other resources dedicated to “breaking in to the industry” (learning and following the rules) than those concerned with breaking it up (tearing up the old rules and making new ones).

Seen from a distance, this phenomenon should strike anyone as odd. After all, you won’t find many young journalists struggling to learn the ropes of the 20th century newspaper trade. Nor is top tech talent lining up for job interviews at Verizon or AOL. But that is, in effect, what many filmmakers are busy doing right now.

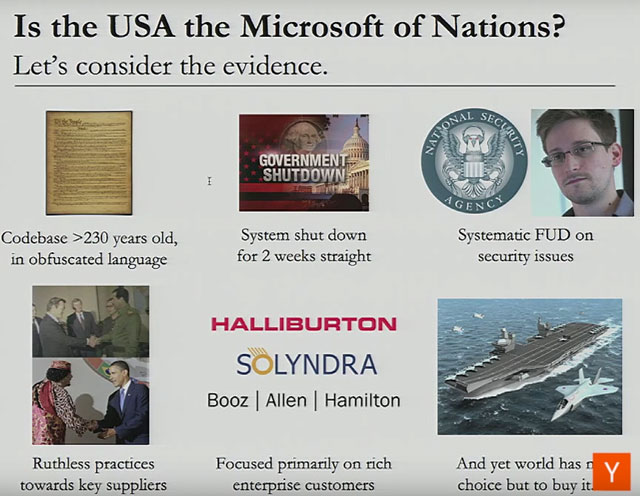

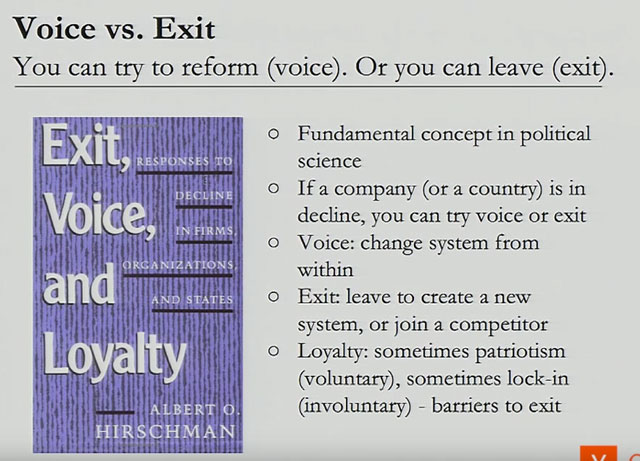

Balaji Srinivasan deftly crystallizes this question as “Voice vs. Exit”. In a 2013 Ycombinator talk, he poses a series of challenging questions, starting with this one: Is America the Microsoft of Nations?

He makes a compelling case.

The question is what to do when an 800-pound, gate-keeping incumbent is blocking your way. Do you bow and scrape for admittance, and then try to reform from within? (The “Voice” route.) Or do you skip the kowtowing, and build your own systems instead? (“Exit.”)

The last two decades have seen the rise of a busy independent film circuit. But it’s worth asking: is getting your film into Sundance or Toronto the first step toward greater artistic and economic independence? Or is it usually a stepping stone to the studio system? By and large, it would seem that the “8th Studio” functions very much like a farm league for Hollywood. The end game is to get called up to the Big Game.

In vibrant growth industries, the smartest creatives tend to head for the exits. But filmmakers, for the most part, are still genuflecting for the old guard’s favor. There are certainly some sound economic reasons behind this:

- Filmmaking, much more than other digital-native ventures, requires large upfront capital investments. I covered this in part 1.

- Traditional “Film” is not a growth industry. (I highly recommend Matthew Ball’s series of essays on this topic.)

- Media production experiences a perpetual oversupply of labor, making it difficult to earn a steady living.

But this phenomenon goes beyond mere economic realities. We are a passionate, sentimental lot. We harbor a reverence for the old masters who forged that Deep Magic long ago. If you’re a gen-Xer, that magic might be embodied in the 20th Century Fox fanfare followed by a Lucasfilm logo. But everyone has their own version of this. It stirs something deep inside of us.

Almost invariably, our own Deep Magic was forged by the old guard’s institutions.

And a big part of us just wants to live up to that. Hey, it’s understandable.

But as long as this remains our highest goal—to run back into Daddy’s arms—we’re just playing the part of supplicants at the temple gates. And as long as we aspire to join the Priestly Caste, it will be that much easier for old power structures to remain intact, and the film industry will continue to ward off true disruption.

Hey, while you're here ...

We wanted you to know that The End Run is published by Endcrawl.com.

Endcrawl is that thing everybody uses to make their end credits. Productions like Moonlight, Hereditary, Tiger King, Hamilton—and 1,000s of others.

If you're a filmmaker with a funded project, you can request a demo project right here.

Why Film has not been Disrupted (Yet), Part 3

We show too much deference toward the old guard. It's time to lose that love affair.