Post Production is a Kung Fu Movie

Part 1: Why there's so much Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Kung Fu

I recently posited a simple premise: Post Production is a lot like a Kung Fu movie.

1/ the post production landscape is like a Kung Fu movie. #postchat #filmmaking #postproduction

— Pliny (@iampliny) May 17, 2016

Every post facility is a dojo unto itself. Each dojo practices its own style: different workflows, different tech, different philosophies. Some dojos have famous sifus. They all employ eager practitioners who diligently memorize their Katas.

And true to the Rival Dojos Trope, each Dojo likes to contend that “The Kung Fu from my Dojo is Superior to the Kung Fu from your Dojo”.

So far, so good: healthy competition is great. In fact, I’ve gone so far as to argue that the film world could use a bit more hip-hop style feuding and the occasional flying elbow. Artists on both sides of the camera calling each other out would sure be an improvement to the endless mutual back-scratching and awards-seasons in-cliques that bedevil us now.

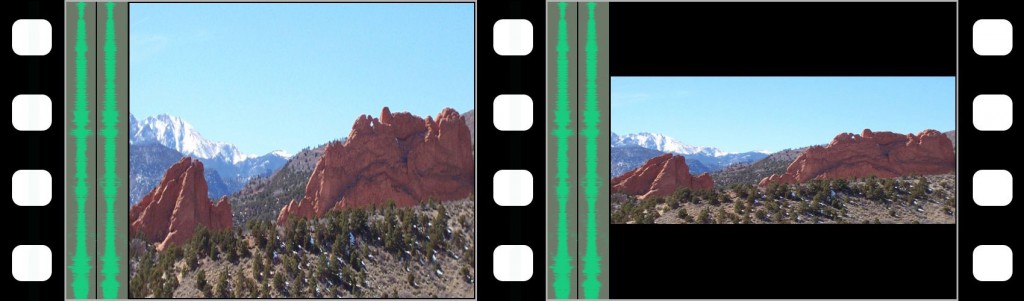

Pictured: a robust exchange of ideas.

But in the world of post production Kung Fu there is a more pernicious tendency that goes well beyond friendly rivalry.

I’m thinking of those Dojos that don’t just consider their Kung Fu better; they consider their Kung Fu to be the One True Path—and by extension, all other Kung Fu to be a confused, crass fallacy.

Ironically, this dogmatism is not only correlated with some of the worst Kung Fu out there; it also emanates more and more from some of the most famous Big Dojos.

If you’ve been around post production for any period of time, you’ve probably stumbled across this hubris already: We are correct because look! at the logo on our door. Please stop asking questions now.

Anamorphic Dreamin’

One brief example.

I was working on a film that had shot a file-based anamorphic format. I’ll spare you the gory details, but at the time, this workflow resulted in original camera media that was 1836 x 1536 pixels. The final outputs, of course, were digital cinema deliverables, which are 2048×858.

For those playing along at home: that’s a 1.8k workflow for a 2k finish. The frame was vertically over-sampled, but it was under-sampled on the horizontal axis.

If you’d like to start a “Bad Workflow” Tumblr, please DM me on Twitter.

Now the precise reason for this raster came down to hardware and signal processing limitations that existed with the hardware at that time. Not a good starting point, but there was nothing the Dojo could do about that.

But the fun part was Big Dojo’s next decision: they mandated that all VFX, titles, and other elements must be delivered in 1.8k as well.

That’s a damned shame.

Also a shame: the hour-long conference call it took just to explain to Big Dojo what they had just done. Upon which they explained, again, what the name of their company was and then quickly ended the call.

Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Kung Fu

So why does so much of the most Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Kung Fu emanate from Big Dojo?

To answer that, we need examine the nature of Big Dojo itself: how it becomes Big in the first place, and how it persists. The next several posts will dive deeper into this. Here’s a preview:

- Big Dojo rises to prominence for all sorts of reasons — and superior Kung Fu is the least of them.

- Big Dojo doesn’t stay in business by offering its clients better Kung Fu. It stays in business by selling its clients job security.

- Big Dojo attracts a certain type of practitioner: call them “city planners” as opposed to “pioneers”.

- Big Dojo erects all sorts of internal incentive structures that catalyze lousy Kung Fu and actively punish good Kung Fu.

I’ll be unpacking this over the next several posts. But let’s start with disabusing ourselves of the idea that Good Kung Fu and Big Dojo must necessarily go hand-in-hand.

If that were true, Microsoft would make the best operating system, McDonald’s would make the tastiest burgers, and the world’s greatest martial artists would all hail from Tiger Shulman’s Karate.

Hey, while you're here ...

We wanted you to know that The End Run is published by Endcrawl.com.

Endcrawl is that thing everybody uses to make their end credits. Productions like Moonlight, Hereditary, Tiger King, Hamilton—and 1,000s of others.

If you're a filmmaker with a funded project, you can request a demo project right here.

Blinded by Color Science

16 SharesShare11Tweet5ShareBufferPocketI recently posited a simple premise: Post...