Videotaping the Revolution

May Day Vietnam Protest in Washington, DC, 1971, via Third Space Network

What do we see when we point the camera at ourselves?

It’s difficult to imagine a world without video sharing platforms like YouTube, Vimeo, Twitch, WorldStarHipHop, Dailymotion, Youku, and yes, even Pornhub. Forget that the legacy film industry considers Internet streaming services like Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon as disruptors — not only do we have more choices for watching films and television than ever before, we’re watching ourselves more than ever.

Let’s rewind the clock to 1967, when Sony introduced the Portapak DV-2400 Video Rover, the first portable video system: a heavy, clunky two-piece set consisting of a large black-and-white video camera and a separate record-only ½” reel-to-reel VTR. (A separate VTR was required for video playback.) The one (sometimes two) person operation was light-years ahead of previous attempts at home video technology, the very first of which was 1963’s 100-pound Ampex VR-1500 video recorder that retailed for $30,000 USD and required an Ampex engineer to set it up for you.

Image used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

At the time, many consumers were still making their own films with Super8 and 16mm film cameras in all the ways we use our smartphones and contemporary video cameras — for private consumption, for sharing with friends — but methods of distribution were limited. Making copies of home movies and independent films (such as they were) was costly, cumbersome, and time-consuming, and as such there was virtually no exhibition platform for these films other than one’s own home projector. Television was another matter.

Television was video: electronic sound and picture recorded to the same magnetic tape, which was easier to edit than film, and could be duplicated over and over again, up to a certain number of generations. You could reuse tape. You could transmit it directly into people’s homes, which in 1960 included 52 million sets — nine out of ten American households. (Compared to only 78 percent of households with a broadband connection in 2015.)

Until what came to be known as the “Portapak Era”, the realm of moving pictures was — and had been since the inception of moving pictures — ruled by a top-down system and controlled by those who owned the means of production as well as its dissemination. This realm includes entertainment and sports, and most significantly, education and the news.

Video may have been relatively easier than film, but it was not cheap. In order to afford the equipment necessary to shoot, edit, duplicate, and distribute video, early adopters formed clubs around the new technology, collectively purchasing and sharing their resources as enthusiasts of the medium’s potential for expression and for its disruptive and democratic nature. Some of the best-known collectives of that the late 1960s/early 1970s were birthed in the coastal hotbeds of counterculture, including New York’s The Kitchen, Fluxus, and the Videofreex, and the SF Bay Area’s Video Free America and the Ant Farm.

In 1969, public access television and cablecasting was made available to videomakers, and it’s easy to imagine the excitement the creators, journalists, educators, and activists of the 1960s must’ve felt when they realized that there was now an alternative to the corporate systems that had for so long controlled the gross media narrative. One could now record a thing that happened — street art, guerrilla theater, a protest, an act of civil disobedience or state violence — and play it back for the world almost immediately.

As portable video technology improved, television news abandoned their complicated film and telecine workflows, opting for the efficiency and raw immediacy provided by videotape, as evidenced by Alan and Susan Raymond’s 1977 documentary The Police Tapes. In a world of tumultuous global politics, the Civil Rights movement, and the existential/sexual/psychedelic revolution, the Portapak was another upheaval — a symbol of autonomy and truth for turned-on, tuned-in filmmakers.

Soon, a vibrant subculture began to spring up around these TV natives, driven by social and political satire, psychedelia, art (spearheaded by the pioneering work of video artists like Nam June-Paik and Shigeko Kubota), and cybernetics; a cinema for the people, by the people.

Much has been written about this social and artistic renaissance, but there are a few key texts that function as its touchstones, chiefly Marshall McCluhan’s The Medium is the Massage (1967). “Societies have always been shaped more by the nature of the media by which men communicate than by the content of the communication,” McCluhan writes. “Wars, revolution, civil uprisings are interfaces within the new environments created by the electronic informational media… The living room has become the voting booth. Participation via television in Freedom marches, in war, revolution, pollution, and other events is changing everything.”

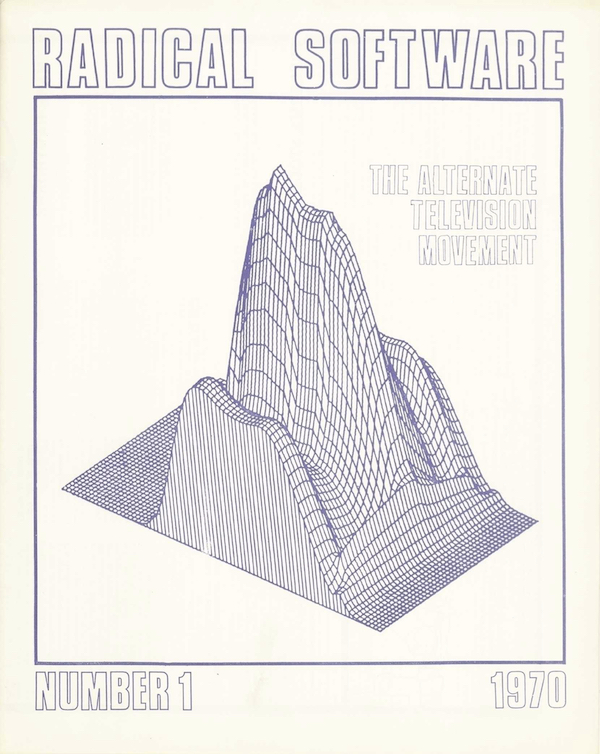

In the spring of that same year, the first issue of Radical Software was created by Phyllis (Gershuny) Segura and video artist Beryl Korot, and ultimately published by the Raindance Corporation “to bring a fresh direction to communication via personal and portable video equipment and other cybernetic explorations.”

“It was thought at one time that through feedback loops and interactivity a platform for self-correction would emerge in the culture, rather than relentless self pre-occupation,” says Segura in a 2015 Rhizome column on the genesis of Radical Software. “Video did enable people to see themselves as if for the first time. You’d look and see and be able to self-correct motions, attitudes and more. It extended the mirror for greater psychological and physical adjustment.”

When Segura writes that she and her contemporaries didn’t envision YouTube or the iPhone it almost sounds like a confession, but the promise of the Portapak Era is alive and well in the Internet Age. Consider the role user-generated video had in boosting the signals of the Arab Spring (launched on Facebook and live-streamed), Occupy Wall Street (they had their own media team), Standing Rock (a virtual mainstream media blackout), and the Black Lives Matter movement (documenting systemic racial violence and police brutality). Many of the shallow and negative aspects of democratized video are worth a single instance of human justice.

Hey, while you're here ...

We wanted you to know that The End Run is published by Endcrawl.com.

Endcrawl is that thing everybody uses to make their end credits. Productions like Moonlight, Hereditary, Tiger King, Hamilton—and 1,000s of others.

If you're a filmmaker with a funded project, you can request a demo project right here.

How Not to Break Into Writing About Film

What do we see when we point the camera at ourselves?