Frame Guides: Meadowland

A visual analysis of Reed Morano, ASC's directorial debut

When an artist pivots toward a new practice, they inevitably bring with them two things: their reputation and their experience. In the case of Meadowland, the feature debut of director Reed Morano, ASC, the filmmaker’s noted reputation arrives intact, and her signature point of view — honed with the cinematography of films like 2013’s Kill Your Darlings and 2008’s Frozen River — is not only present, it achieves a kind of apotheosis. (Ed. Note: Meadowland used Endcrawl, which publishes this site.)

Meadowland is a drama about the different ways that two New York City parents cope with the sudden disappearance of their young son. A year later, the boy is still missing and the father, a policeman named Phil (played by Luke Wilson), longs for closure while the mother, a schoolteacher named Sarah (played by Olivia Wilde), clings to a thread of hope that their child is still alive. They’re in the same boat, rocking on a sea of depression, and rowing in different directions — he to shore, and she into deeper, deadlier waters.

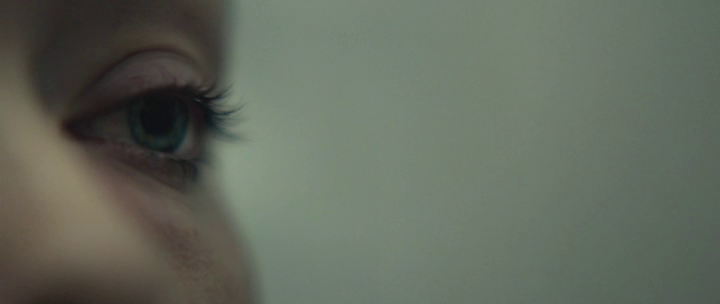

Morano’s vibrant, kinetic photography — with its frequently shallow focus and handheld camera — is like the filmic equivalent of a gesture drawing. There’s something unreal and distinctively graphic about its representation, but there’s a truth in its shape, the details, the colors, the quality of the light.

Meadowland functions not merely in cinematic and narrative terms — it’s also an object of pure creative expression. The only lens through which we are told this story is Morano’s, and through it we observe the hazy impressions of ghosts, of memories, of people. As the film progresses, it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish one from the other. Sarah and Phil, Phil’s addict brother (Giovanni Ribisi), his friend in the support group (John Leguizamo), the hustler at the gas station (Elisabeth Moss), the student with Asperger’s, the girl in Sarah’s class who cuts herself: each character occupies a shallow, liminal space — call it a personal hell — that’s both in and out of focus, between light and shadow, day and night.

“I’m not a dark person by nature,” says Morano in a 2015 interview (conducted by this writer) for American Cinematographer, “but I always thought that if I directed a movie, I wanted to make something that would punch people in the gut.”

“This story begged for a naturalistic approach, so the look didn’t require a ton of obsessing.”

“I wanted to be wide open for aesthetic reasons. In some scenes, like the ones showing Sarah out in public, I wanted the world to feel like a foreign place, and I used the shallow depth of field to isolate her from everyone else.”

“The only way this film could work is if viewers believe this is real, that they’re totally with these characters.”

“I’m looking for the moments that explain everything someone is feeling, with absolutely no dialogue.”

“I took more risks. I didn’t overthink things… And if I wanted no fill light, no one on set was going to disagree.”

“I didn’t want the colors to be too punchy or to feel too digital, so I restricted the color space in the dailies, then [Company 3] colorist Andrew Geary and I brought it back in the DI.”

“I care about the emotion first and the shot second,” Moreno concludes. “On Meadowland I committed more to the story and the actors than the cinematography, and I feel this is my best work as a cinematographer.”

Hey, while you're here ...

We wanted you to know that The End Run is published by Endcrawl.com.

Endcrawl is that thing everybody uses to make their end credits. Productions like Moonlight, Hereditary, Tiger King, Hamilton—and 1,000s of others.

If you're a filmmaker with a funded project, you can request a demo project right here.

How I Write About Film

A visual analysis of Reed Morano, ASC's directorial debut.