Why Film has not been Disrupted (Yet), Part 5

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

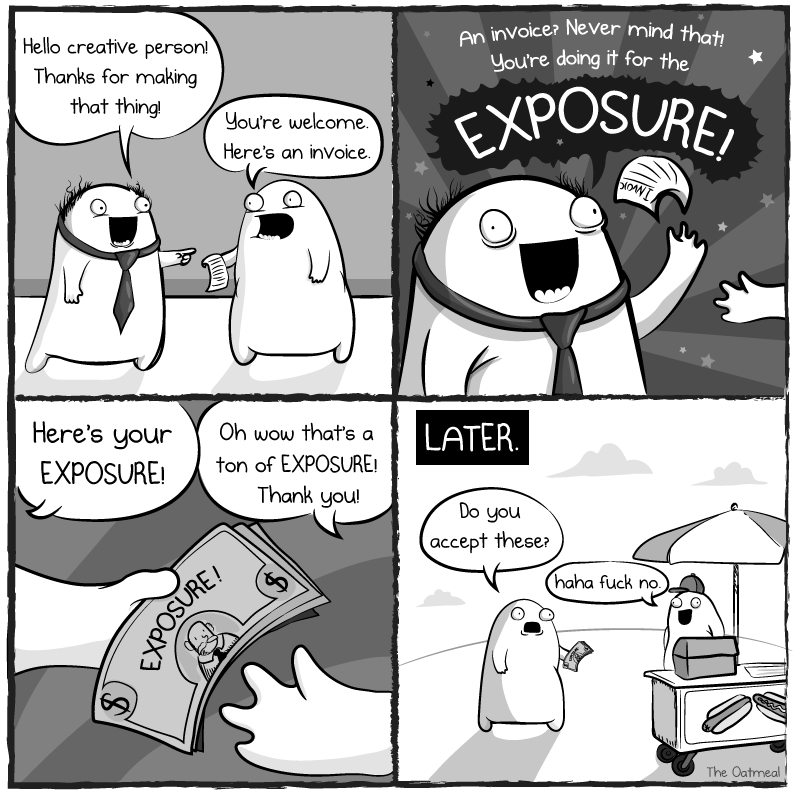

The film industry is damned good at assimilating and neutralizing its top talent.

This is the final post in a series asking why the film industry has resisted disruption so far:

- Making a movie is still an all-or-nothing proposition.

- Film technologists are focusing on all the wrong areas.

- Filmmaking is (computationally) expensive.

- We are a deeply traditional, conservative, and sentimental lot.

- The film industry neutralizes its best and brightest.

- Postscript: There Are Always Two Revolutions

5. The film industry neutralizes its best and brightest.

I like to draw a lot of comparisons between the tech and film industries. Not just because I straddle those two worlds, but because they also inform each other a lot.

But while the tech industry has long been defined those who chose Exit instead of Assimilation (going back to the Traitorous Eight) the opposite dynamic is in effect over here in la-la-land.

Welcome to the Indie-Go-Round

I’ve previously commented on the sobering experience of watching “established” industry pros live out a grind-and-hustle lifestyle well into their 50s and 60s.

You think that plateau of stable, fulfilling work is right over the horizon? That the right mixture of grit and cheery attitude will lead you there? That rarely pans out.

You see, it’s a permanent buyer’s market. Show business emanates powerful reality distortion fields that are always able to pull in fresh bodies. Don’t like your working conditions? Just peek over your shoulder: there are at least two dozen snowflakes queued up behind you. And they can’t wait to take their lumps.

And so many of us find ourselves, at one point in our careers, on the dread Indie-Go-Round Of Death: you’ll take your movie to a few festivals, walk a red carpet perhaps, do a Q&A panel or two. If you’re lucky, maybe a photo-op with Robert Redford.

Then it’s back to borderline poverty, and you get to do it all over again.

@MatthewACherry each year I get jelly of my friends with movies in Sundance. Right up until April, when they call me looking for a job.

— Pliny (@iampliny) April 29, 2016

And then it'll blow away a couple hundred people who catch it on whatever SVOD service bought distribution rights for pennies on the dollar. https://t.co/xVzBFOkyoZ

— Keith Calder (@keithcalder) November 7, 2016

Rearguard Actions

But a few of us—with the right combination of hard skills, personal charisma, and dumb fucking luck—do manage to grab on to a small piece of arbitrage or staying power. In a nearly 100% elastic marketplace, that’s a powerful thing.

That arbitrage can take different forms: an output deal, a corporate gig, personal connections with the investor class, a trust fund, a key relationship with a rising star, or early access to some other form of New Hotness.

Once you’ve gained that edge, there is a natural tendency to flip from a posture of openness—which was to your advantage when you were still up and coming—to a posture of gate-keeping. And why not? After years of struggle, how does it benefit you personally to “disrupt” a beast that has finally doled out your small fief? Best to hunker down, pull your punches, and play defense. Kind of like a soccer team protecting a narrow 1-0 lead in a really boring World Cup match.

The film industry, it turns out, is exceptionally good at assimilating and neutralizing its best and brightest.

Where would the tech industry be if every engineer’s highest aspiration was landing a gig with Verizon? We’d be approximately where the film business is right now. Instead of exiting and innovating, our biggest “rock stars” often turn out to be our biggest reactionaries. Finally granted a small taste of inner-circle status, they are successfully recruited into waging rearguard actions to preserve the elderly status quo.

And so we find ourselves in a business that not merely resists but preemptively and successfully suppresses any meaningful disruption.

#NotAllRockstars

Hands up if you’ve been guilty of some of this.

It’s a question worth asking: Am I trying to innovate, or gate-keeper?

In an bid to close out this series on a positive note, I want to highlight a few people who have a good answer to the above question. Not content to circle the wagons, these individuals have leveraged their success into platforms to innovate, empowering their colleagues along the way:

- Katie Hinsen is a world-class finishing artist. Her resume includes Avatar and District 9. She’s worked at companies like Light Iron Digital and Peter Jackson’s Park Road. In her spare time, Katie founded the Blue Collar Post Collective, a non-profit that promotes inclusion and accessibility for emerging post production talent.

- Evan Schiff is currently editing John Wick 2. He’s also busy publishing a collection of web-based workflow tools for his video editors—including a Letterbox Generator and an EDL to SubCaps converter. These are 100% free, by the way. What did you do this week?

- Steve Yedlin is a self-described “cameraman” who recently published a massive study entitled “On Color Science For Filmmakers”. Read it. Now it’s possible Steve just wanted to drum up some publicity for his next gig, since he recently wrapped his latest “camerama” job. That film’s working title is “Star Wars 8.”

- Stu Maschwitz defies summary but I’ll give it a shot: ten years ago he published the seminal “DV Rebel’s Guide”, following that up with his empowering prolost blog. Currently Creative Director at Red Giant, Stu’s provenance includes ILM and The (Late, Great) Orphanage. Stu is one-half of Slugline, and has been a vocal booster for technologies like fountain.io (Markdown for screenplays) and Courier Prime (a better font for screenwriters).

Re-focusing Outward

Everyone in this cherry-picked list has at least one thing in common: an outward focus. Innovation rarely happens in a vacuum, and it never happens in an Old Boys’ Club.

There are many reasons the film industry has resisted disruption so far. But our biggest hurdles remain the mental and cultural ones.

I started this series by quoting Esko Kilpi: “The Internet is nothing less than an extinction-level event for the traditional firm.” Studios are not teflon. Incumbents go broke “first slowly, then all at once.” We’re still watching the first half of that sentence unfold, but the signs are all over the place:

13/ I'll be told this is alarmist, but again, getting pretty hard to escape this gravitational pull. How far to event horizon? pic.twitter.com/HMnPx1Up8b

— Matthew Ball (@ballmatthew) October 17, 2016

The smartest old-media dignitaries understand this, and are just trying to run out the clock on their careers before the real changes hit.

You probably don’t have that luxury.

True disruption in the film industry will not come from Silicon Valley, which has steadfastly failed to understand the dynamics underpinning media creation. Nor will it come from filmmakers who consistently mis-classify “disruption” as small, tactical improvements to old workflows and business models.

Disruption will come when smart creatives from both camps find ways to link up and do something altogether new.

But first, filmmakers have re-orient themselves. That will involve doing some hard things. Like ditching love affairs with the past. Prioritizing good work above status-seeking. And engaging more openly with our peers.

John Boyd once said that you can either Be Someone, or you can Do Something. There’s your choice.

I know, I know: most of us would jump at the opportunity to work Star Wars 9. But frankly, I have bigger plans.

So should you.

Hey, while you're here ...

We wanted you to know that The End Run is published by Endcrawl.com.

Endcrawl is that thing everybody uses to make their end credits. Productions like Moonlight, Hereditary, Tiger King, Hamilton—and 1,000s of others.

If you're a filmmaker with a funded project, you can request a demo project right here.

How To Get The On-Screen Credit You Deserve

The film industry is damned good at assimilating--and neutralizing--its top talent.